Burials

Human remains are found throughout the settlement of Monjukli Depe. They offer insights into the local practices involving the dead in the early Aeneolithic. During our recent excavations 15 graves were excavated, 13 of which are associated with the Aeneolithic settlement. One grave dates to the Middle Bronze Age.

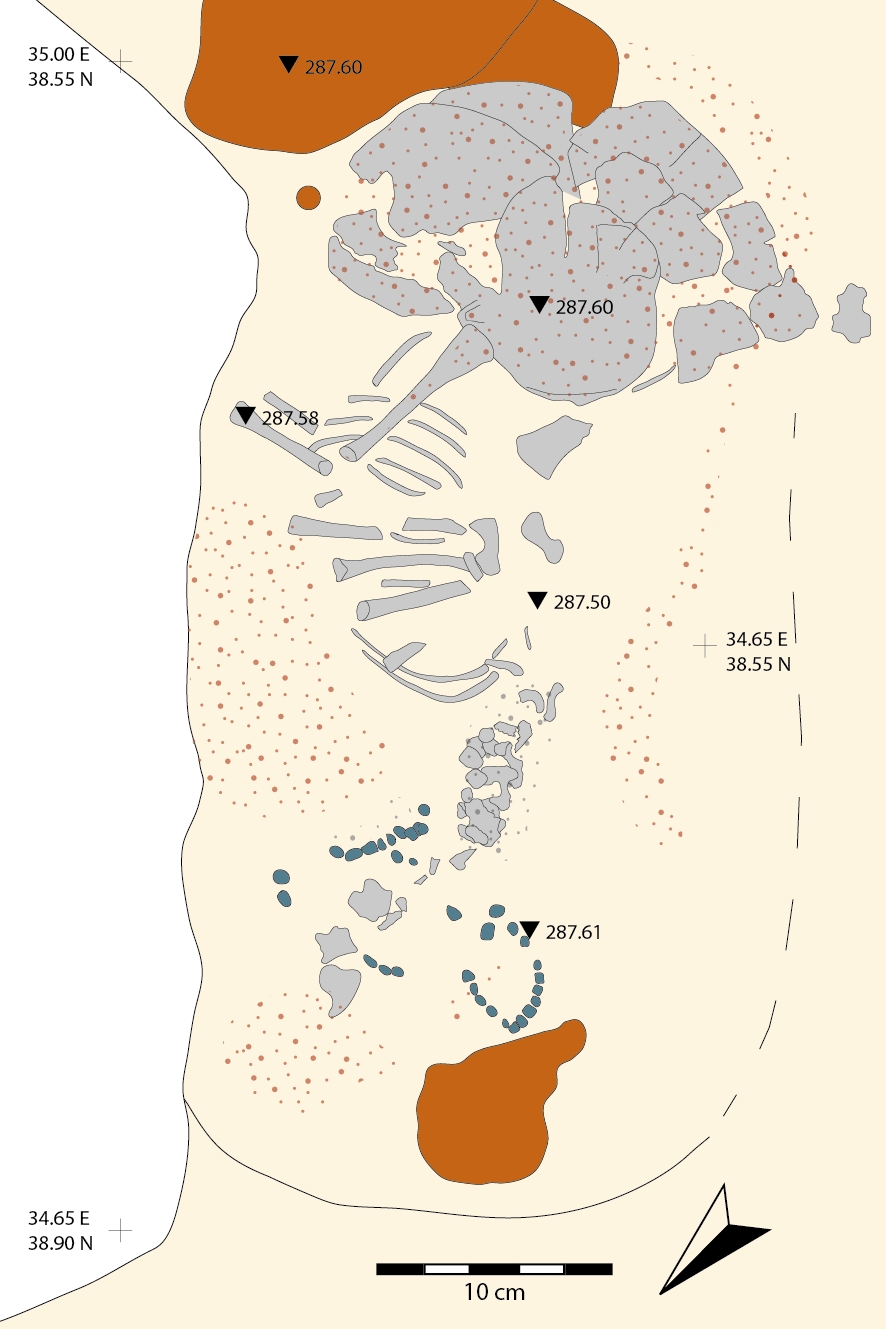

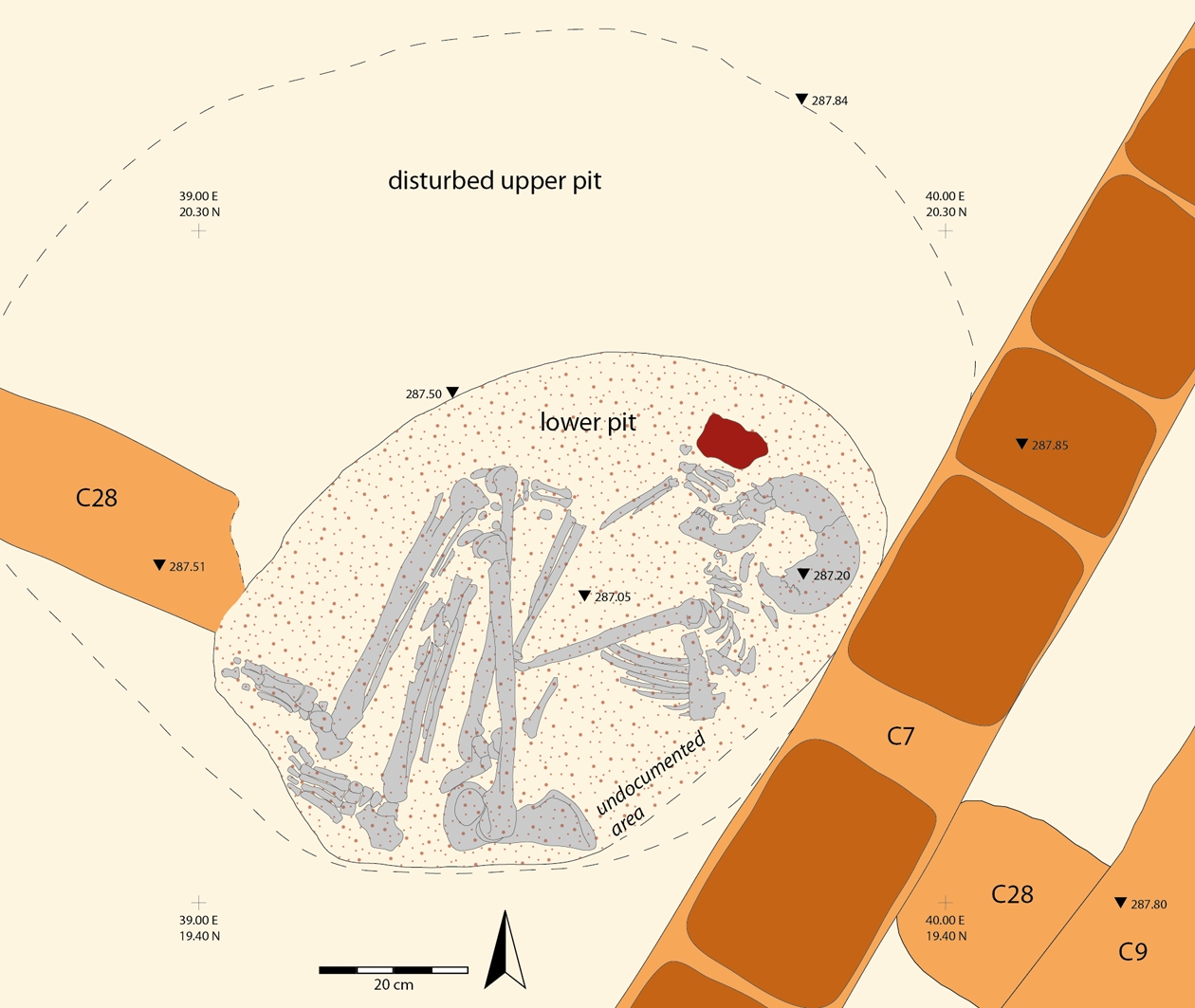

As a rule, the Aeneolithic burials are comprised of single, primary inhumations in earthen pits. In two cases one or more infants were buried together with an adult. We could distinguish four different forms of graves: shallow pit graves; rudimentary shaft graves with a funnel or L-shaped profile; earthen pits with a ring of brick fragments; and interments without pits that rather appear to consist of a heap of debris. The deceased were buried in a flexed position, generally on the right side. The body and/or the grave pit were generally pigmented with ocher, and the body was often wrapped in a shroud of vegetal material, possibly a plaited mat. Grave goods are scarce, if present at all, and the array of grave goods used was not standardized. Burials of adults include ecofacts such as stones and animal bones or occasionally chipped stone blades, whereas burials of younger individuals contain on occasion beads or a token.

Graves can be found in variable contexts in the settlement: over or under floors, in abandoned buildings, or below outdoor surfaces. Many of the burials appear to have been closely connected to the life-cycle of the houses, whether in the form of a foundation deposit or as part of a ritual closure of the house. It may also be that a death was the trigger for building activities.

Isolated human skeletal parts that occur in various settlement contexts can only rarely be connected to intentional practices, but they do point to a habitual engagement with human remains and possibly to an everyday, "profane" understanding of dead bodies.

Routine practices and observed deviations from them permit us to identify social tendencies and to estimate the degree of leeway for individuals and groups to modify burial practices for their individual members. Primary inhumation in an earthen pit, in a flexed position, and on the right side appear to be norms that, with only few exceptions, structured the way of disposing of the dead. The regular use of ocher shows that use of pigment was very much favored, but it does not appear to have been mandatory in all cases. In the choice of the place to inter the dead, the age of the deceased played a decisive role. Adult burials in occupied houses were avoided, whereas foundation deposits consisted exclusively of fetuses or new-born infants. Other practices associated with burials show, in contrast, greater variability, for example the direction of the body, the ocher-bearing material basis, the position of the arms, or the burial sequence. For each burial an array of idiosyncratic practices together with their meanings came into the picture.

The small number of burials shows that only a fraction of the population, probably 5-10%, were interred within the settlement. In other words, one can speak of a normative minority practice. The question remains open as to how the majority of the dead were treated and on which basis the choice was made of whom to bury within the village. For the most recent graves, it can be presumed that the village had already been abandoned and the site had gone through a change of function to turn it into a graveyard.

For further reading, see Rol in Pollock et al. (eds.) 2019.